The World War II Era: Exploring the Evolution of Canadian Transit from 1934-1945

As Canada emerged from the Great Depression into World War II, urban transit evolved significantly against a backdrop of economic hardship and global conflict. CUTA continued to play a crucial role in shaping the country’s transportation landscape.

In the 1930s, Canadian National Railways faced a unique challenge: trains needed shorter smokestacks to navigate tunnels, but the reduced height impaired engineer visibility at higher speeds. To address operating safety concerns, the trains were operated at slower speeds, and passengers complained of slower travel. In response, CNR turned to the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) for a solution.

Harnessing the power of its new wind tunnels, the NRC tested aerodynamic models of existing trains and proposed alternative designs. The result? By 1936, the sleek 6400 locomotive was ready to, safely, speed across Canadian railways. Its debut at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City catapulted it to instant fame, with locomotives bearing its likeness appearing on tracks worldwide for decades.

Meanwhile, Minister of Railways, Clarence Decatur Howe embarked on a mission to reform Canada’s transportation system. The Transport Act of 1936 established the first federal Department of Transport under Howe’s leadership, laying the groundwork for modern transportation governance. In 1938, the creation of the Board of Transport Commissioners further solidified these reforms.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 brought new challenges, but despite the upheaval of war, Canada’s transportation industry thrived as demands for wartime logistics surged.

In 1942, as war activities intensified, the demand for transportation surged across all industries. With natural rubber supplies cut off and gasoline deliveries curtailed, there was a noticeable decrease in automobile usage and a corresponding increase in the reliance on mass transportation. So much so that the industry faced the overwhelming problem of overcrowding. This shift brought unprecedented public attention to the transit industry, with the public recognizing the critical role of transit. CUTA, then the Canadian Transit Association (C.T.A.), prompted the official acknowledgment and implementation of relief measures such as staggered work hours and traffic congestion management.

In June 1942, CUTA held its 38th Annual Meeting at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto, where our association gathered to emphasize the role of public transit in supporting war production. Recognizing transit as a war industry vital to defeating the Axis powers, CUTA stressed the need for efficient transit operations amidst manufacturing constraints and overcrowding.

The Advertising and Sales Committee published the following quote in the Annual Report presented at the 38th Annual Meeting.

“When we hear again those prophetic words “Cease fire!” and the last echo dies around the world- when industry is changing from war to peacetime productions, then much will have to be done to retain patronage. We must be prepared to use everything we have to hold our trade- but publicity alone is not sufficient.”

During this time, transit training and hiring practices adapted to meet the demands of the workforce. New guidelines were implemented, including the consideration of men under 35 years of age only if they had rejection papers from the army. Height and weight requirements were also adjusted to accommodate a broader pool of applicants. The minimum height was lowered from 5’6 to 5’5 and the minimum weight was lowered to 135 lbs.

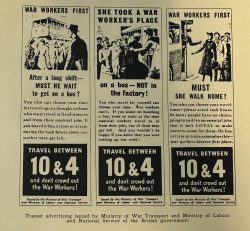

The Ministry of War Transport, and the Ministry of Labour and National Service of the British Government launched a campaign to raise awareness about the challenges faced by war workers during rush hour. Eye-catching graphics were designed to encourage the public to avoid using public transit during peak times to alleviate overcrowding and ensure war workers could commute to and from their jobs without added stress. The campaign sought to foster a sense of public responsibility towards those undertaking essential roles in Canada’s war efforts.

Image 1: “War Workers First” campaign from the Canadian Transit Association’s 38th Annual Reports of Committees

In June 1943, at the 39th annual meeting held at the Mount Royal Hotel in Montreal, transit leaders continued to emphasize the crucial role of public transit in supporting war workers. They underscored the importance of government endorsement in prioritizing the transportation needs of those contributing to the war effort. CUTA put forth the recommendation to approach the Department of Munitions and Supply to address the pressing issue of transporting munition workers efficiently. This call to action highlighted the collective responsibility to ensure that essential workers could commute to and from their jobs with ease during wartime.

By the war’s end in 1945, most public transit systems in Canada needed extensive investment to address aging infrastructure. The decline in demand for public transit accompanied by the rise of automobiles prompted cities across Canada to replace older streetcar services with modern trolleybuses and motorbuses. Toronto, however, opted to retain its streetcars, setting the stage for future transit innovations.

Despite the challenges of war, Canada’s transportation sector emerged stronger and more resilient, laying the groundwork for future advancements in public transit and urban mobility. As the nation transitioned to peacetime, the lessons learned from wartime transportation initiatives continued to shape the evolution of Canada’s transportation infrastructure for decades to come.